The Original Nine. Js

The original nine. js

More Posts from Xnzda and Others

HCG 87: A Small Group of Galaxies : Sometimes galaxies form groups. For example, our own Milky Way Galaxy is part of the Local Group of Galaxies. Small, compact groups, like Hickson Compact Group 87 shown above, are interesting partly because they slowly self-destruct. Indeed, the galaxies of HCG 87 are gravitationally stretching each other during their 100-million year orbits around a common center. The pulling creates colliding gas that causes bright bursts of star formation and feeds matter into their active galaxy centers. HCG 87 is composed of a large edge-on spiral galaxy visible near the image center, an elliptical galaxy visible to its right, and a spiral galaxy visible near the top. The small spiral near the center might be far in the distance. Several stars from our Galaxy are also visible in the foreground. Studying groups like HCG 87 allows insight into how all galaxies form and evolve. via NASA

js

THE UNIVERSE SAID TRANS RIGHTS!! 🗣🗣

Bright stars of Sagittarius and the center of our Milky Way Galaxy lie just off the wing of a Boeing 747

js

Cosmic rays

Cosmic rays provide one of our few direct samples of matter from outside the solar system. They are high energy particles that move through space at nearly the speed of light. Most cosmic rays are atomic nuclei stripped of their atoms with protons (hydrogen nuclei) being the most abundant type but nuclei of elements as heavy as lead have been measured. Within cosmic-rays however we also find other sub-atomic particles like neutrons electrons and neutrinos.

Since cosmic rays are charged – positively charged protons or nuclei, or negatively charged electrons – their paths through space can be deflected by magnetic fields (except for the highest energy cosmic rays). On their journey to Earth, the magnetic fields of the galaxy, the solar system, and the Earth scramble their flight paths so much that we can no longer know exactly where they came from. That means we have to determine where cosmic rays come from by indirect means.

Because cosmic rays carry electric charge, their direction changes as they travel through magnetic fields. By the time the particles reach us, their paths are completely scrambled, as shown by the blue path. We can’t trace them back to their sources. Light travels to us straight from their sources, as shown by the purple path.

One way we learn about cosmic rays is by studying their composition. What are they made of? What fraction are electrons? protons (often referred to as hydrogen nuclei)? helium nuclei? other nuclei from elements on the periodic table? Measuring the quantity of each different element is relatively easy, since the different charges of each nucleus give very different signatures. Harder to measure, but a better fingerprint, is the isotopic composition (nuclei of the same element but with different numbers of neutrons). To tell the isotopes apart involves, in effect, weighing each atomic nucleus that enters the cosmic ray detector.

All of the natural elements in the periodic table are present in cosmic rays. This includes elements lighter than iron, which are produced in stars, and heavier elements that are produced in violent conditions, such as a supernova at the end of a massive star’s life.

Detailed differences in their abundances can tell us about cosmic ray sources and their trip through the galaxy. About 90% of the cosmic ray nuclei are hydrogen (protons), about 9% are helium (alpha particles), and all of the rest of the elements make up only 1%. Even in this one percent there are very rare elements and isotopes. Elements heavier than iron are significantly more rare in the cosmic-ray flux but measuring them yields critical information to understand the source material and acceleration of cosmic rays.

Even if we can’t trace cosmic rays directly to a source, they can still tell us about cosmic objects. Most galactic cosmic rays are probably accelerated in the blast waves of supernova remnants. The remnants of the explosions – expanding clouds of gas and magnetic field – can last for thousands of years, and this is where cosmic rays are accelerated. Bouncing back and forth in the magnetic field of the remnant randomly lets some of the particles gain energy, and become cosmic rays. Eventually they build up enough speed that the remnant can no longer contain them, and they escape into the galaxy.

Cosmic rays accelerated in supernova remnants can only reach a certain maximum energy, which depends on the size of the acceleration region and the magnetic field strength. However, cosmic rays have been observed at much higher energies than supernova remnants can generate, and where these ultra-high-energies come from is an open big question in astronomy. Perhaps they come from outside the galaxy, from active galactic nuclei, quasars or gamma ray bursts.

Or perhaps they’re the signature of some exotic new physics: superstrings, exotic dark matter, strongly-interacting neutrinos, or topological defects in the very structure of the universe. Questions like these tie cosmic-ray astrophysics to basic particle physics and the fundamental nature of the universe. (source)

Five-dimensional black hole could 'break' general relativity

Cambridge UK (SPX) Feb 19, 2016 Researchers have shown how a bizarrely shaped black hole could cause Einstein’s general theory of relativity, a foundation of modern physics, to break down. However, such an object could only exist in a universe with five or more dimensions. The researchers, from the University of Cambridge and Queen Mary University of London, have successfully simulated a black hole shaped like a very thi Full article

The Carina Nebula - A Birthplace Of Stars

The Carina Nebula lies at an estimated distance of 6,500 to 10,000 light years away from Earth in the constellation Carina. This nebula is one of the most well studied in astrophysics and has a high rate of star formation. The star-burst in the Carina region started around three million years ago when the nebula’s first generation of newborn stars condensed and ignited in the middle of a huge cloud of cold molecular hydrogen. Radiation from these stars carved out an expanding bubble of hot gas. The island-like clumps of dark clouds scattered across the nebula are nodules of dust and gas that are resisting being eaten away by photons (particles of light) that are ionizing the surrounding gas (giving it an electrical charge).

Credit: NASA/Hubble

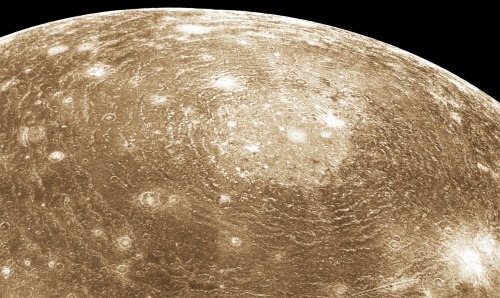

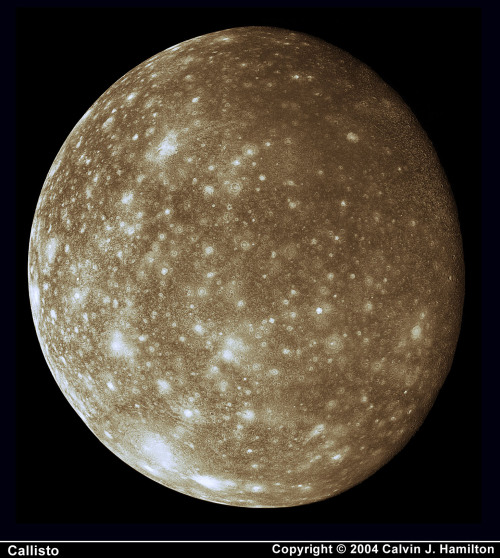

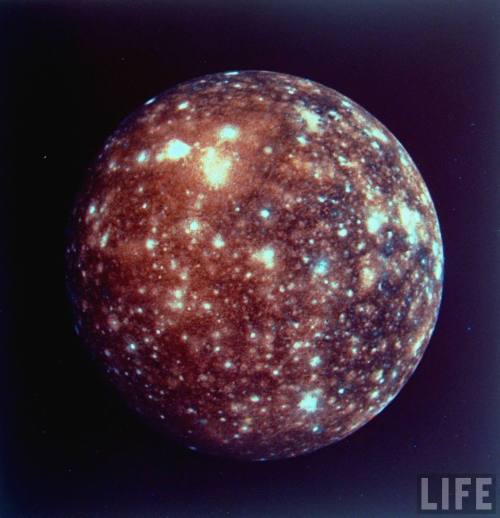

Jupiter’s moon, Callisto.

-

jabz-93 liked this · 2 months ago

jabz-93 liked this · 2 months ago -

this-ishappiness reblogged this · 2 months ago

this-ishappiness reblogged this · 2 months ago -

this-ishappiness liked this · 2 months ago

this-ishappiness liked this · 2 months ago -

sleep1essnights reblogged this · 2 months ago

sleep1essnights reblogged this · 2 months ago -

lunasdiiary liked this · 2 months ago

lunasdiiary liked this · 2 months ago -

fullofnightnoises reblogged this · 2 months ago

fullofnightnoises reblogged this · 2 months ago -

brunobrza liked this · 2 months ago

brunobrza liked this · 2 months ago -

canser-be-r-o reblogged this · 2 months ago

canser-be-r-o reblogged this · 2 months ago -

twistedsolitude reblogged this · 2 months ago

twistedsolitude reblogged this · 2 months ago -

468h4c liked this · 2 months ago

468h4c liked this · 2 months ago -

embracedflaws reblogged this · 2 months ago

embracedflaws reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sufiblackmamba reblogged this · 2 months ago

sufiblackmamba reblogged this · 2 months ago -

sufiblackmamba liked this · 2 months ago

sufiblackmamba liked this · 2 months ago -

nikpik15 liked this · 2 months ago

nikpik15 liked this · 2 months ago -

mess-ines reblogged this · 2 months ago

mess-ines reblogged this · 2 months ago -

relax-mode reblogged this · 2 months ago

relax-mode reblogged this · 2 months ago -

kafaminguzelligi reblogged this · 2 months ago

kafaminguzelligi reblogged this · 2 months ago -

yelenasvestpockets liked this · 2 months ago

yelenasvestpockets liked this · 2 months ago -

peabraininavat reblogged this · 2 months ago

peabraininavat reblogged this · 2 months ago -

purpledazzlefruit liked this · 2 months ago

purpledazzlefruit liked this · 2 months ago -

xlucyintheskyy liked this · 2 months ago

xlucyintheskyy liked this · 2 months ago -

treasuredpleasures reblogged this · 2 months ago

treasuredpleasures reblogged this · 2 months ago -

shannoneichorn liked this · 2 months ago

shannoneichorn liked this · 2 months ago -

my-mind-body-and-soul reblogged this · 2 months ago

my-mind-body-and-soul reblogged this · 2 months ago -

ohuwantsomeofthishotfire reblogged this · 2 months ago

ohuwantsomeofthishotfire reblogged this · 2 months ago -

itshaslove reblogged this · 2 months ago

itshaslove reblogged this · 2 months ago -

slavic-empress liked this · 2 months ago

slavic-empress liked this · 2 months ago -

barmulh reblogged this · 2 months ago

barmulh reblogged this · 2 months ago -

glittergoldmoney reblogged this · 2 months ago

glittergoldmoney reblogged this · 2 months ago -

dopecaliqueen liked this · 2 months ago

dopecaliqueen liked this · 2 months ago -

bigdaddyangelica liked this · 2 months ago

bigdaddyangelica liked this · 2 months ago -

aljouharaa reblogged this · 2 months ago

aljouharaa reblogged this · 2 months ago -

aljouharaa liked this · 2 months ago

aljouharaa liked this · 2 months ago -

eryoufah reblogged this · 2 months ago

eryoufah reblogged this · 2 months ago -

prettyblacktaurus reblogged this · 2 months ago

prettyblacktaurus reblogged this · 2 months ago -

mademoiselleteetee reblogged this · 2 months ago

mademoiselleteetee reblogged this · 2 months ago -

el-hijo-desobediente reblogged this · 2 months ago

el-hijo-desobediente reblogged this · 2 months ago -

thankmelaterx3 liked this · 2 months ago

thankmelaterx3 liked this · 2 months ago -

thankmelaterx3 reblogged this · 2 months ago

thankmelaterx3 reblogged this · 2 months ago -

cultural-derealization liked this · 2 months ago

cultural-derealization liked this · 2 months ago -

lemme-holla-at-you reblogged this · 2 months ago

lemme-holla-at-you reblogged this · 2 months ago -

aurora-bore-aura reblogged this · 2 months ago

aurora-bore-aura reblogged this · 2 months ago -

aurora-bore-aura liked this · 2 months ago

aurora-bore-aura liked this · 2 months ago -

luniimunii27 liked this · 2 months ago

luniimunii27 liked this · 2 months ago -

zelianthos-capercaillie liked this · 2 months ago

zelianthos-capercaillie liked this · 2 months ago -

official--superman reblogged this · 2 months ago

official--superman reblogged this · 2 months ago -

amoremvao liked this · 2 months ago

amoremvao liked this · 2 months ago -

aounce liked this · 2 months ago

aounce liked this · 2 months ago