The Sky Seemed To Smile Over Much Of Planet Earth. Visible The World Over Was An Unusual Superposition

The sky seemed to smile over much of planet Earth. Visible the world over was an unusual superposition of our Moon and the planets Venus and Jupiter. A crescent Moon over Los Angeles appears to be a smile when paired with the planetary conjunction of seemingly nearby Jupiter and Venus.

More Posts from Venusearthpassage and Others

'Sail-Rover' could make Venus exploration possible.

NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts program is funding a study into the possible use of a sail powered rover to explore the 500°C surface temperatures of Venus.

Read More

Could we create dark matter?

85% of the matter in our universe is a mystery. We don’t know what it’s made of, which is why we call it dark matter. But we know it’s out there because we can observe its gravitational attraction on galaxies and other celestial objects.

We’ve yet to directly observe dark matter, but scientists theorize that we may actually be able to create it in the most powerful particle collider in the world. That’s the 27 kilometer-long Large Hadron Collider, or LHC, in Geneva, Switzerland.

So how would that work? In the LHC, two proton beams move in opposite directions and are accelerated to near the speed of light. At four collision points, the beams cross and protons smash into each other.

Protons are made of much smaller components called quarks and gluons.

In most ordinary collisions, the two protons pass through each other without any significant outcome.

However, in about one in a million collisions, two components hit each other so violently, that most of the collision energy is set free producing thousands of new particles.

It’s only in these collisions that very massive particles, like the theorized dark matter, can be produced.

So it takes quadrillions of collisions combined with theoretical models to even start to look for dark matter. That’s what the LHC is currently doing. By generating a mountain of data, scientists at CERN are hoping to find more tiny bumps in graphs that will provide evidence for yet unknown particles, like dark matter. Or maybe what they’ll find won’t be dark matter, but something else that would reshape our understanding of how the universe works entirely.

And that’s part of the fun at this point. We have no idea what they’re going to find.

From the TED-Ed Lesson Could we create dark matter? - Rolf Landua

Animation by Lazy Chief

NASA is developing a rover for Venus that could survive the planet’s tumultuous atmosphere.

A Sun Pillar over Norway via NASA https://ift.tt/2Hnj1WZ

Pioneer Venus Artwork

Artist’s concept of Pioneer Venus mission approaching the planet.

During a 14-year orbit of Venus, Pioneer Venus 1 used radar to map the surface at a resolution of 75 km (47 miles). It found the planet to be generally smoother than Earth, though with a mountain higher than Mt. Everest and a chasm deeper than the Grand Canyon. The orbiter also found Venus to be more spherical than Earth, consistent with the planet’s much slower rotation rate (one Venus day equals 243 Earth days). It confirmed that Venus has little, if any, magnetic field and found the clouds to consist mainly of sulfuric acid. Measurements of this chemical’s decline in the atmosphere over the course of the mission suggested that the spacecraft arrived soon after a large volcanic eruption, which may also account for the prodigious lightning it observed.

After a course correction on 16 August 1978, Pioneer Venus 2 released the 1.5-m diameter large probe on 16 November 1978, at about 11.1 million km from the planet. Four days later, the bus released the three small probes while 9.3 million km from Venus. All five components reached the Venusian atmosphere on 9 December 1978, with the large probe entering first.

Data from the probes indicated that between 10 and 50 km, there is almost no convection in the Venusian atmosphere. Below a haze layer at 30 km, the atmosphere appears to be relatively clear. Amazingly, two of three probes survived the hard impact. The so-called Day Probe transmitted data from the surface for 67.5 minutes before succumbing to the high temperatures and power depletion.

Credit: NASA/Rick Guidice

Solar System: Things to Know This Week

Go for Venus! Fifty-five years ago this week, Mariner 2, the first fully successful mission to explore another planet launched from Cape Canaveral in Florida. Here are 10 things to know about Mariner 2.

1. Interplanetary Cruise

On August 27, 1962, Mariner 2 launched on a three and a half month journey to Venus. The little spacecraft flew within 22,000 miles (about 35,000 kilometers) of the planet.

2. Quick Study

Mariner 2’s scan of Venus lasted only 42 minutes. And, like most of our visits to new places, the mission rewrote the books on what we know about Earth’s sister planet.

3. Hot Planet

The spacecraft showed that surface temperature on Venus was hot enough to melt lead: at least 797 degrees Fahrenheit (425 degrees Celsius) on both the day and night sides.

4. Continuous Clouds

The clouds that make Venus shine so bright in Earth’s skies are dozens of miles thick and permanent. It’s always cloudy on Venus, and the thick clouds trap heat - contributing to a runaway “greenhouse effect.”

5. Night Light

Those clouds are why Venus shines so brightly in Earth’s night sky. The clouds reflect and scatter sunlight, making Venus second only to our Moon in celestial brightness.

6. Under Pressure

Venus’ clouds also create crushing pressure. Mariner 2’s scan revealed pressure on the surface of Venus is equal to pressure thousands of feet under Earth’s deepest oceans.

7. Slow Turn

Mariner 2 found Venus rotates very slowly, and in the opposite direction of most planets in our solar system.

8. Space Travel Is Tough

Mariner 2 was a remarkable accomplishment, considering that in 1962 engineers were still in the very early stages of figuring out how operate spacecraft beyond Earth orbit. The first five interplanetary missions launched - by the U.S. and Soviet Union, the only two spacefaring nations at the time - were unsuccessful.

9. Not Ready for Its Close Up

Mariner 2 carried no cameras. The first close-up pictures of Venus came from NASA’s Mariner 10 in 1974.

10. Hot Shot

The first (and still incredibly rare) photo of the surface of Venus was taken by the Soviet Venera 9 lander, which survived for a little more than a minute under the crushing pressure and intense heat on the ground.

Make sure to follow us on Tumblr for your regular dose of space: http://nasa.tumblr.com

“Anyone who has never made a mistake has never tried anything new.” - Albert Einstein

“Venus at Night in Infrared from Akatsuki” Is the NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day of today, January 30, 2018

Daily Science Dump: Kepler’s First Law Edition

Bonjour my science nerds. I got a question regarding Kepler’s Three Laws because they can be somewhat confusing. And tbh, they really are. Because they can be a bit of a pain, I’ve decided to break this up into 3 sections, one for each law. They generally follow the same idea: planetary orbits are not circular. The difference between each law resides in the minute details. And because they are really detailed, I wanted to make sure I covered everything of each law so they don’t get confused. Let’s get started!

Kepler’s First Law of Planetary Motion

History

Before we get into the actual laws, we need to understand why these laws are so important. During the 1500s and early 1600s, astronomy was starting to become a big deal. We were trying to figure out where we are in the universe. During this time period, the famous geocentric and heliocentric models were stirring up massive controversy in the Catholic Church (for obvious reasons). Ptolemy brought around the geocentric model, which put Earth at the center. This was a natural thought at the time because it was a religious concept that man was God’s greatest creation, so God would want to put man at the center of everything (little presumptuous on our part tbh). Next, Copernicus said that our Sun was in the center, and all the planets orbit around the sun. This clearly didn’t go down well with the Church because it was the first instance of defying the Catholic Church, therefore defying God. In an attempt to settle down the controversy, Brahe brought around a new theory model, putting the Earth at the center, having the Sun and Moon orbiting the Earth, and then the rest of the planets orbiting the Sun. It was a very far reached model but people bought it. All of these models had one thing in common; all the orbits of the planets were circular. But none of none of the actual data fit with perfect circular orbits. This is where our boi Kepler comes in.

It was long believed that the planets should orbit along circular paths, because a circle is considered an ideal shape. But as I mentioned before, none of the data was fitting the circular shape, particularly Mars. Kepler brought around another shape, the ellipse, to explain the missing pieces of the data. An ellipse is like a flattened circle with some important properties that Kepler used for his laws. His first law focuses more on explaining the patterns of elliptical orbits. The second and third law goes into more detail on the properties of elliptical orbits.

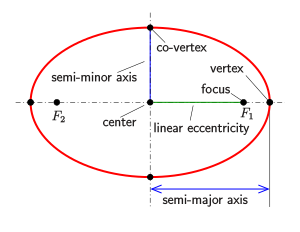

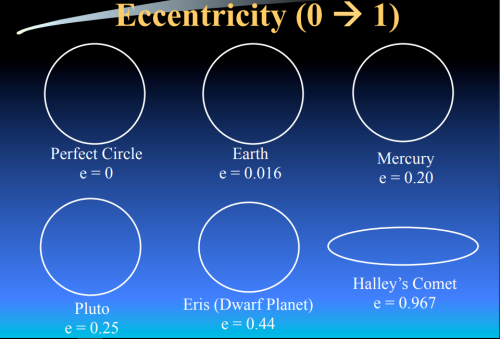

If you’ve taken a simple geometry class, you know the basic principles of ellipses. We know there’s a major-axis and minor-axis (the diameter horizontally and the diameter vertically), the focal points, and eccentricity. All of these are important for planetary orbits. If we take a trip back to geometry, we know that the positions of the focal points affect the eccentricity, which is basically how much it’s being squished (if e = 0 then it’s a perfect circle and if e = 1 it’s a parabola).

All of this geometry going on transfers over into planetary motion. In this case, the Sun acts as one of the focal points. The other focal point is merely imaginary. Mathematically it exists but there’s nothing at that point in space that says “Hey! I’m a focal point for Saturn!”. But we know for sure that the Sun is on of the two focal points. This revelation caused a lot of uproar and many refused to believe it. Partly because the orbit of a lot planets are so close to a perfect circle it’s extremely hard to tell it’s elliptical at all.

Eccentricity has to stay between 0 and 1, like I explained earlier. An eccentricity of 0 is a perfect circle. If it’s 1 or greater, it’s a parabola. For the planetary motion, most of the planets’ eccentricity doesn’t even crack 0.1 (Pluto has a bit over 0.2 but apparently Pluto isn’t a planet #JusticeForPluto). Earth’s eccentricity is currently 0.0167, which means its very very close to a perfect circle. But not quite. To be quite honest, the fact that Kepler was able to figure out that the orbits were not circular is astonishing.

So that’s it for Kepler’s First Law of Planetary Motion! These laws were critical in understanding how our universe works and how our solar system plays out. It opened our eyes to many new ideas and thought processes. This law is just the first step of understanding the orbital tendencies of planets. On Friday, we will dive right into Kepler’s Second Law of Planetary Motion which goes into detail about the speed of the planet due to the elliptical orbit.

Don’t forget, I’m updating the Blog Website everyday with something new because I have no life…. I added cool space music! If you have any cool song recommendations for the playlist definitely shoot me a message!

If you have any questions about today’s Daily Science Dump or any past ones, don’t be afraid to ask!

As always,

Stay Nerdy!

R.L.

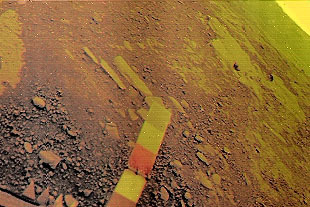

Venera

The Venera series space probes were developed by the Soviet Union between 1961 and 1984 to gather data from Venus, Venera being the Russian name for Venus. As with some of the Soviet Union’s other planetary probes, the later versions were launched in pairs with a second vehicle being launched soon after the first of the pair.

Ten probes from the Venera series successfully landed on Venus and transmitted data from the surface of Venus, including the two Vega program and Venera-Halley probes. In addition, thirteen Venera probes successfully transmitted data from the atmosphere of Venus.

Among the other results, probes of the series became the first human-made devices to enter the atmosphere of another planet (Venera 4 on October 18, 1967), to make a soft landing on another planet (Venera 7 on December 15, 1970), to return images from the planetary surface (Venera 9 on June 8, 1975), and to perform high-resolution radar mapping studies of Venus (Venera 15 on June 2, 1983). The later probes in the Venera series successfully carried out their mission, providing the first direct observations of the surface of Venus. Since the surface conditions on Venus are extreme, the probes only survived on the surface for durations varying between 23 minutes (initial probes) up to.

source

-

thetoxicgirl96 liked this · 6 years ago

thetoxicgirl96 liked this · 6 years ago -

corsetsgirdlesnylons liked this · 6 years ago

corsetsgirdlesnylons liked this · 6 years ago -

imurderedtheklller liked this · 6 years ago

imurderedtheklller liked this · 6 years ago -

palestpupkit reblogged this · 6 years ago

palestpupkit reblogged this · 6 years ago -

existentialimperfection reblogged this · 6 years ago

existentialimperfection reblogged this · 6 years ago -

existentialimperfection liked this · 6 years ago

existentialimperfection liked this · 6 years ago -

jamous reblogged this · 6 years ago

jamous reblogged this · 6 years ago -

jamous liked this · 6 years ago

jamous liked this · 6 years ago -

moonchildoxo reblogged this · 6 years ago

moonchildoxo reblogged this · 6 years ago -

doyoumakeyourselfproud reblogged this · 6 years ago

doyoumakeyourselfproud reblogged this · 6 years ago -

dammarxo reblogged this · 6 years ago

dammarxo reblogged this · 6 years ago -

dammarxo liked this · 6 years ago

dammarxo liked this · 6 years ago -

pvnk-bitch reblogged this · 6 years ago

pvnk-bitch reblogged this · 6 years ago -

jeansticks reblogged this · 6 years ago

jeansticks reblogged this · 6 years ago -

pcychologymajor reblogged this · 6 years ago

pcychologymajor reblogged this · 6 years ago -

satansskunt reblogged this · 6 years ago

satansskunt reblogged this · 6 years ago -

anonymousclone liked this · 6 years ago

anonymousclone liked this · 6 years ago -

k-popcorneaters reblogged this · 6 years ago

k-popcorneaters reblogged this · 6 years ago -

k-popcorneaters liked this · 6 years ago

k-popcorneaters liked this · 6 years ago -

rabbit-habits reblogged this · 6 years ago

rabbit-habits reblogged this · 6 years ago -

rabbit-habits liked this · 6 years ago

rabbit-habits liked this · 6 years ago -

chvsingdizvster reblogged this · 6 years ago

chvsingdizvster reblogged this · 6 years ago -

craigvicious reblogged this · 6 years ago

craigvicious reblogged this · 6 years ago -

stardust-savior reblogged this · 6 years ago

stardust-savior reblogged this · 6 years ago -

stardust-savior liked this · 6 years ago

stardust-savior liked this · 6 years ago -

idkidkidk111-blog liked this · 6 years ago

idkidkidk111-blog liked this · 6 years ago -

palestpupkit liked this · 6 years ago

palestpupkit liked this · 6 years ago -

mr-curious90 reblogged this · 6 years ago

mr-curious90 reblogged this · 6 years ago -

mr-curious90 liked this · 6 years ago

mr-curious90 liked this · 6 years ago -

nvox liked this · 6 years ago

nvox liked this · 6 years ago -

i-see-mixed-people-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago

i-see-mixed-people-blog reblogged this · 6 years ago -

djsuicide203 liked this · 6 years ago

djsuicide203 liked this · 6 years ago -

smokeddoutchuckbeatz liked this · 6 years ago

smokeddoutchuckbeatz liked this · 6 years ago -

ka-deity reblogged this · 6 years ago

ka-deity reblogged this · 6 years ago -

countdorkulaspit liked this · 6 years ago

countdorkulaspit liked this · 6 years ago -

brightersideofthesoul reblogged this · 6 years ago

brightersideofthesoul reblogged this · 6 years ago -

brightersideofthesoul liked this · 6 years ago

brightersideofthesoul liked this · 6 years ago -

psy-faerie reblogged this · 6 years ago

psy-faerie reblogged this · 6 years ago -

eridanu-s reblogged this · 7 years ago

eridanu-s reblogged this · 7 years ago